Reclaiming the Stories of Care Systems of Rural Black North Carolinians

Daud Malik is a chemistry and public policy major in the class of 2028 and a featured guest blogger. Daud was a student in our human rights seminar course, Memory Bandits, in fall 2025. This seminar introduced students to multiple approaches to why and how to create memory, with a focus on contributing to a project underway at Catawba Trail Farm. Several students will be featured guest bloggers on the Duke Human Rights Blog this month as part of our Student Stories: Memory Bandits Series.

When I first started learning about the memory bandit idea, it felt distant from the rest of my academic work. At Duke, I spend my time drowned in the world of regulatory health reform, child policy initiatives, and therapeutics. As time passed, I learned memory bandits work to reclaim the stories that systems of power have tried to erase.

The concept became much clearer to me at the Stagville historic site and Catawba Trail Farm. Working to dismantle systems that try to erase or control the past are relevant to the same health infrastructure that I plan to follow as a career. Both memory and medicine involve systems that were once designed to exclude many people. In the future, both require care, persistence, and attention to what has been lost and erased.

I researched the history of care systems in Durham. Specifically, how did formerly enslaved people and their descendants in rural North Carolina – particularly sharecroppers and small farmers – access, create, and sustain healthcare systems during the 19th century, especially in contrast to urban Black communities? Among my sources are oral histories, early 19th and 20th century maps, the work of historians like Sydney Nathans, and Duke Medical Center Library’s Archives.

It’s no secret that enslaved people had little to no access to professional health care. Usually, there were solely systems of care that included healers who learned their skills from elders. However, one unusual case is Virgil Bennehan. Virgil was an enslaved man who worked on the Stagville Plantation and may have been the son of both the owner, Thomas, and an enslaved woman, according to historian Sydney Nathans.

Born into slavery in 1808, Virgil uniquely learned to read from his alleged white father. Virgil kept plantation records and later trained directly under white physicians from nearby Hillsborough. Through years of observation and practice, he became the plantation’s resident medic, treating hundreds of enslaved people with skill and empathy.

Through Thomas Bennehan’s will in 1847, Virgil’s family was the sole family freed. With a gift of five hundred dollars, Virgil sailed to Liberia. At the time, Liberia was a young Black republic created through the American Colonization Society, which resettled free African Americans in West Africa under the belief that they could not thrive within the United States. Once there, Virgil settled in Monrovia and later in Bassa Cove, where he continued to practice medicine among settlers who faced disease, food shortages, and unstable trade. His 1848 letter records how he treated the sick daily, writing, “The sick are many, and I do what I can. My hand is not idle, but my purse is empty.”

I felt inspired reading his records. The moment Virgil was known to have gained the education to support other’s wellbeing, he did not hesitate regardless of his personal status or wealth within his communities.

For many Duke students interested in community medicine, they may find themselves involved with work at the Lincoln Hospital, without knowing its remarkable history. Until 1901, formerly enslaved people were segregated out of most care in white institutions. Founded in 1901 as Lincoln Hospital by Dr. Aaron McDuffie Moore and Dr. Stanford L. Warren, both prominent figures on Durham’s Black Wall Street, worked to change that by founding Lincoln Hospital, by and for Black people.

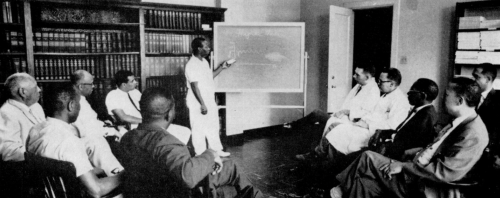

In addition to providing outpatient care, Lincoln served as a training ground for Black medical professionals and as a hub for public health outreach. The Journal of the National Medical Association notes that Lincoln’s staff organized public health programs throughout Durham County, expanding access to maternal care, led sanitation efforts, and sponsored vaccination drives in rural areas.

In 1971, Lincoln became Lincoln Community Health Center, and to this day pursues a mission of service to low-income and uninsured county residents.

Whether it was Virgil Bennehan opening space for the enslaved to care for themselves and their loved ones, to Dr. Moore who created economic growth for his community through medical training and rural outreach, to today, where a black community initiative in Lincoln Hospital continues to support underinsured and working-class families in Durham, the story remains the same. Healthcare in Durham that has served and uplifted Black communities has consistently grown from Black leadership.