The Duke Human Rights Center at the Franklin Humanities Institute (DHRC@FHI) has partnered with the Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice to host a series of professional development workshops for educators in North Carolina, centered around the topic of human rights. “The Righting Wrongs workshops came out of a desire to support teachers in teaching about human rights in their classrooms, and go beyond the idea that ‘rights are something we have that can’t be taken away,’” explains Frances Starn, workshop designer/leader and high school educator. The series works toward providing effective methods for teaching contemporary political and policy issues from a historical perspective, understanding the role played by human rights. The goal, according to Robin Kirk, faculty co-director of the DHRC@FHI and professor of cultural anthropology, is “to try to bring human rights out of the classroom and into the world.”

Human rights (or a lack thereof) are embedded into every era of human history, making them profoundly impactful on the institutions that govern our societies. Many issues that currently harm the wellbeing of students, such as public education, debt, and welfare policies, can be better addressed by policymakers with deep historical understandings of said issues. Thus, it is vital for students, who ultimately become the nation’s leaders and decision makers, to understand these issues as well. The use of curriculums that ingrain the value of human rights are vital in encouraging students to implement those principles in their daily lives and, ultimately, in their professional careers.

While teachers are often well-versed in the factual knowledge surrounding the specific historic events their curriculums cover, there is a variety of contextual and cultural nuance that many teachers are unfamiliar with. This can be especially true for educators that teach historical lessons about North Carolina and Durham, despite not being from this area. These workshops provide information and resources that help close this gap, enabling teachers to better understand and connect with their students. Annabelle Webb, a teacher at Hillside High School, comments on the value of these workshops for white educators teaching students of color. She states, “[The workshops] allow us…to engage with genuine issues that our students of color face, despite the fact that we will never fully know their lived experiences.”

The current program involves a series of three workshops, each focused on a different aspect of human rights in North Carolina’s history. The first workshop, held on March 2, 2024, featured the Museum of Durham History. The second, which took place on April 1, was centered around the topic of voting rights history in North Carolina. Finally, there is a planned workshop on May 10 and will include a representative from Historic Stagville, N.C.’s largest pre-Civil War plantation.

These workshops are a unique yet vital source of professional development, providing educators with methods to implement the teaching of human rights in their classrooms. They are exposed to a variety of resources and learning activities, many of which are later taken straight to the classroom. John Becker, a civics teacher at the Early College High School on Campus at North Carolina Central, reflected on his experience at the workshop, stating that he implemented some of the suggested activities in his classroom the very next day.

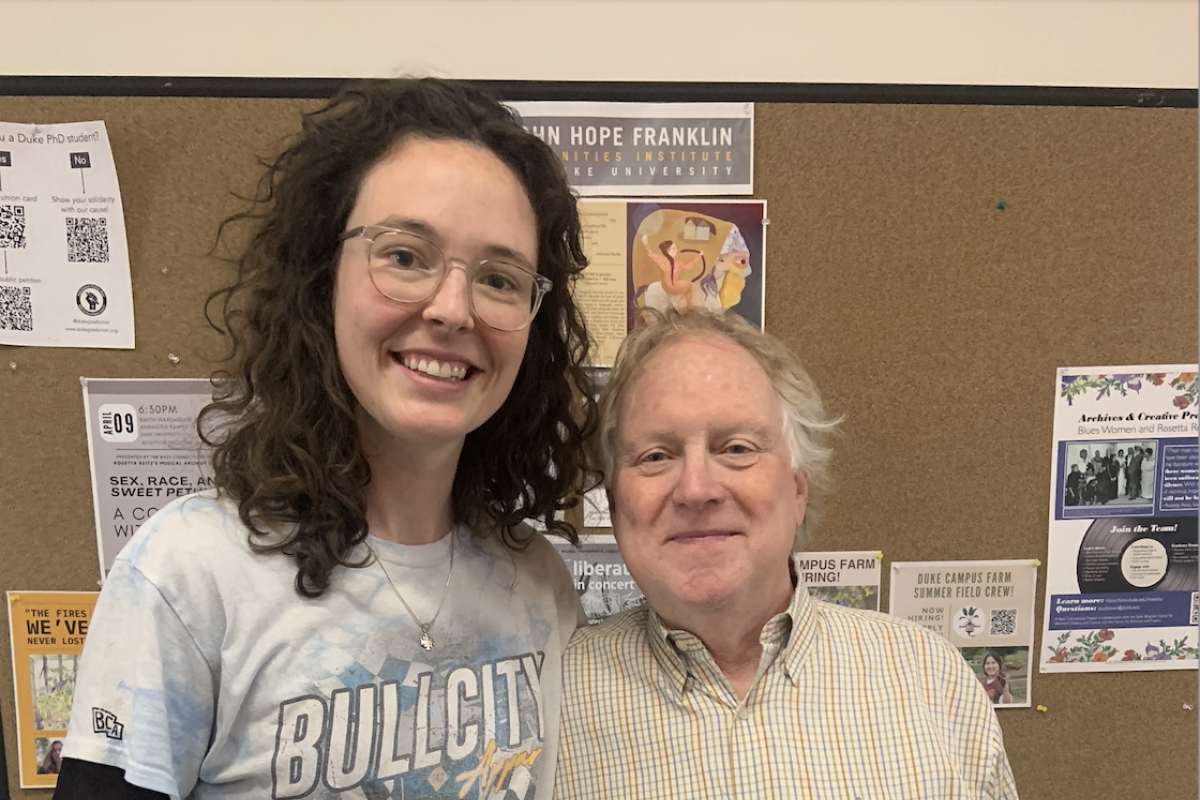

The enriching activities attendees participate in also allow educators to enhance their personal understanding of the topics being discussed. The first session featured presentations by the Museum of Durham History and the Pauli Murray Center. In the most recent workshop, Robert Korstad, a historian and professor of Public Policy and History, provided a short lecture on the history of voting rights in North Carolina, as outlined in his book, Fragile Democracy.

In addition to learning from experts, educators are given the opportunity to learn from each other through the workshops. They make use of small group sessions in which teachers are able to talk to each other and learn from their different experiences as educators. This allows them to compare the different schools, grades, and experiences they have, providing a unique and rewarding mechanism of learning.

In the end, these workshops are not just important for select teachers and their students, but for the entire Durham community. While there are only about 10-15 people at each session, organizers are confident that there will be a “trickle down effect,” and the lessons from the sessions will eventually reach a wider audience. Korstad states, “Issues can be talked about in the classroom, and then maybe students talk to people in their family and friend groups.” Ultimately, the ability of these workshops to get citizens of all ages engaged in the complexities of our political and social system, connecting them to the nation’s history, is a solid step forward. As Frances Starn explains, “This curriculum and these workshops give teachers the opportunity to put our history as North Carolinians at the center of their practice, and show students that they can continue the legacies of activism that are so present in our community.”